Retail Council of Canada (RCC) represents Canadian grocers from coast to coast to coast battling inflation and the ongoing developments surrounding it. In response to recent reports, RCC has prepared the following fact sheet to shed light on what’s really happening in Canadian retail when it comes to inflation.

RECENT STATEMENTS:

The cause of inflation is not Canadian grocery

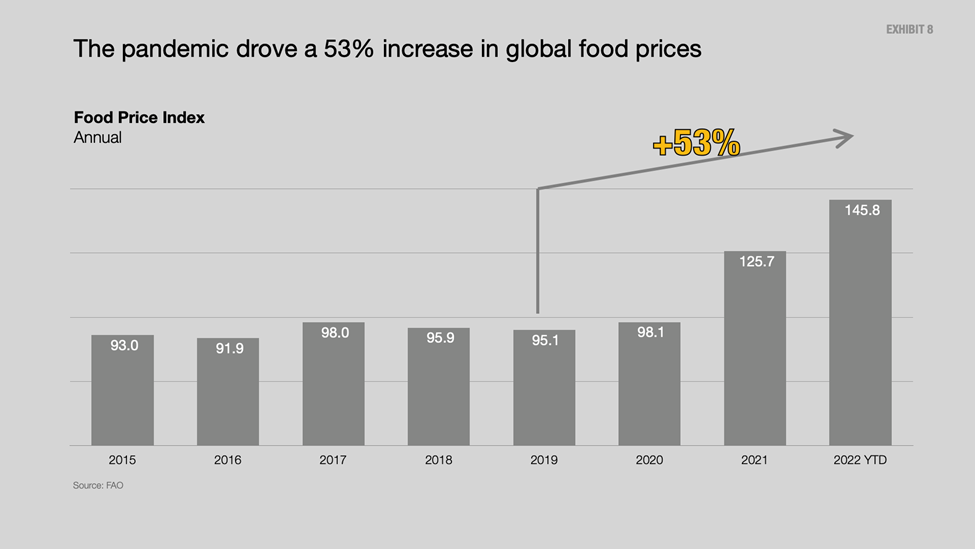

Inflation is being felt up and down the supply chain and across the economy. In the case of food, war, extreme weather, fuel prices, supply chain disruptions, labour shortages, and the weakness of the Canadian dollar caused food prices to rise. There has been lots of evidence of this, including through Statistics Canada, that show the true impact of this international phenomenon.

Grocers are food distributors. They buy goods from suppliers and sell them to customers. There are only so many tools that can be utilized at this end of Canada’s food market as the cost pressures arrive much earlier in the process.

- The reason that prices have risen on grocery shelves is a straightforward one: suppliers – the manufacturers, processors, and wholesalers of food – have been increasing costs of products they supply to retailers repeatedly and almost across the board. That is overwhelmingly the biggest driver of higher prices on the shelf. Why are suppliers’ prices rising so rapidly? Because suppliers’ own costs have soared, driven by unprecedented price increases from farmers, growers, and importers. These, in turn, have been caused by massive cost increases for fertilizer, fuel, and feed, amongst other inputs.

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine crashed grain and fertilizer exports from these leading producers and drove up the price of those commodities. And grain is critical – not only for staples such as bread, pasta, cereals, and cooking oils, but also as feed for most animals raised for meat or for producing eggs and dairy. Grain is also the base for the majority of products in the core aisles of grocery stores. In the same timeframe, scorching weather and drought have hammered fruit and vegetable-producing regions in the North American West on which Canada most relies, especially in California. This has driven up the cost not only of fresh produce, but also canned, frozen, and preserved vegetables and fruits, as well as sauces, juices, and anything in which these are ingredients.

Grocers are not making additional profits on food

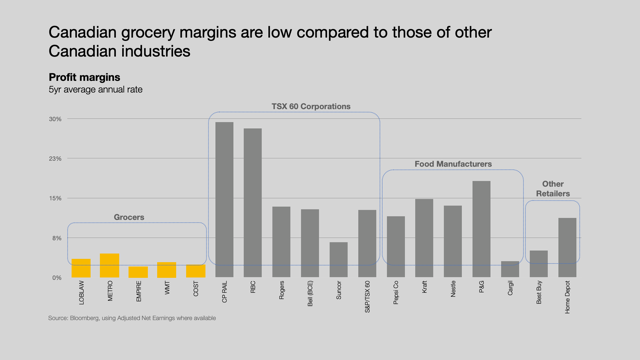

Grocery has, and always will be, a low-margin industry. The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it inflation and an altered consumer, who spent more on products in the pharmacy, health, and beauty aisle rather than food. Grocery margins – averaging around 3.5% – are lower than Canadian net farm income (2021) of 7.4% and significantly lower than margins for food manufacturers and processors.

- Grocery profits are increasingly driven not by food but by items in health, beauty, and pharmacy. Grocers report food profits as flat and some have stated that they are not passing on the full extent of price increases from the manufacturers and processors to their customers. Simply put, these grocers report on what they sell. The range of products is diverse, as any shopper will know from a visit to the grocery store, whether that be household paper, cleaning products, health and beauty, pharmacy, housewares, or pet supplies, among many other categories.

- Grocery margins in Canada are lower than those of other Canadian retailers and industries. Grocer earnings of around 3.5% on average are among the lowest among Canadian industries and are eclipsed by those of most of the food manufacturers, especially the big global CPG companies, whose earnings are several multiples higher.

Canada’s grocery is not a tight market

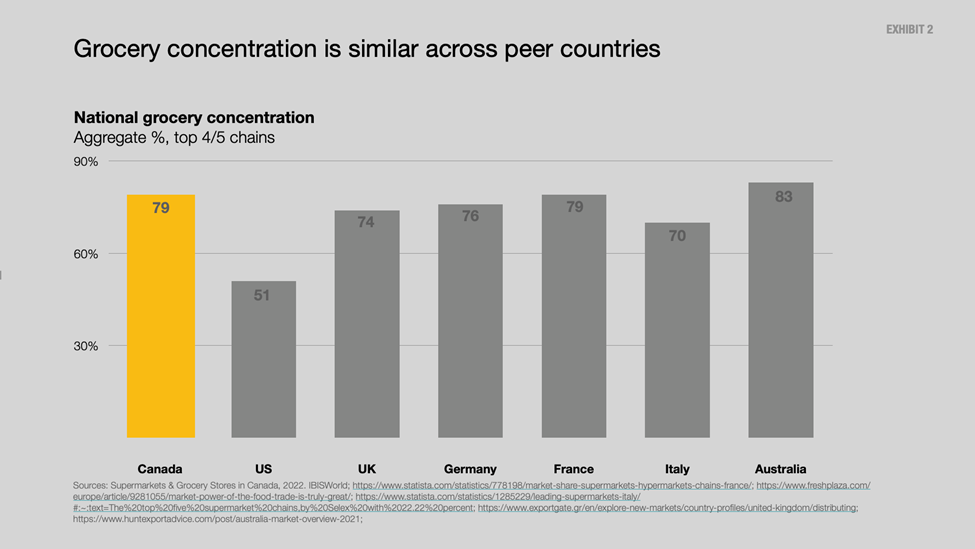

Canada does not have a concentrated grocery sector despite criticisms to the contrary. Canadian consumers, especially in urban and suburban settings, have diverse choices for grocery purchases from grocers of varied sizes and formats. This has been proven repeatedly, especially in contrast to other countries.

Canada’s grocery market share for the top five players is comparable to the market share of the top five players in each of France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Italy.

- Canadian consumers, especially in urban and suburban settings, have diverse choices for grocery purchases from grocers of varied sizes and formats. Canada has three large grocers: Loblaw, Sobeys and Metro, plus big box retailers Costco and Walmart. Four of these are truly national in reach, whereas Metro is focused on Ontario and Quebec. There are other sizeable regional players of which Overwaitea is the most prominent, a number of independent grocers, including independent chains like Rabba, convenience stores, Dollarama, Giant Tiger, Whole Foods, etc., making any suggestion of a lack of competition within Canadian grocery sector misguided.

- There is a large number of independent grocers in Canada, offering yet another option for Canadians to meet their shopping needs, as these independents generally provide more unique and targeted offerings to please shoppers who are looking for a differentiated experience. The Canadian Federation of Independent Grocers (CFIG) represents approximately 6900 independent grocery retailers across Canada (in some cases with cross-membership with Retail Council of Canada), which for a Canadian population base of 39 million averages out to one for every 5640 citizens.

- The competitive dynamics in the grocery market in Canada is also better than that in several other consumer-facing industries. Banking and Telecommunications are notable examples. The “Big Five” banks have 89% of the Canadian banking market and the three largest telecommunications firms have 89% market share of wireless telecommunications. The top five players in grocery, by contrast, have a 79% market share. While these are not directly comparable markets, we believe that it is reasonable to assert that the vast majority of Canadians have far more diverse choices in grocery than in many other spending decisions and are apt to exercise those choices across a wider range of grocers.

What RCC is saying in the media

‘Some of the most aggressive price cutters in the world can’t compete in Canada’

Karl Littler, Senior Vice President, Public Affairs at RCC, speaks to retail’s perspective in response to the Competition Bureau report (CTV NEWS/June 26, 2023)

‘There was an element of opportunity in the blaming of grocers’

Karl Littler, Senior Vice President, Public Affairs at RCC, speaks to the cooling of inflationary pressures and their impact on retail. (BNN Bloomberg/June 23, 2023)

What industry experts are saying

“Over a 5-year period since 2018, general food price inflation has seen an increase of 25.1%, in contrast to the international average of 36.3%. Generally speaking, Canada has fared better than the majority of countries in the study in terms of how inflation has affected their food costs.”

Ubuy

“Ottawa initially embraced the concept of ‘greedflation’ until MPs engaged with experts in the food industry, gaining a deeper understanding of the situation. As a result, the recently released report suggests that Parliament should prioritize other more urgent matters. Thrilled to have contributed to this study where our sources were acknowledged by the committee. The report confirms that Canada’s grocery sector is not experiencing “greedflation”.”

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois, Agri-Food Analytics Lab, Dalhousie University

“Food prices have risen due to multiple factors that have put upward pressure on costs along the food supply chain. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many factors have impacted prices at the grocery store, such as supply chain disruptions, labour shortages, changes in consumer purchasing patterns, poor weather in some growing regions, tariffs, higher input costs, and higher wages. Unlike past trends, many of these conditions and pressures have been occurring simultaneously or in a more pronounced manner, leading to broad-based increases in food prices.”

Statisics Canada

“The competitive dynamics in the grocery market in Canada is also better than that in several other consumer-facing industries. Banking and Telecommunications are notable examples. The “Big Five” banks have 89% of the Canadian banking market and the three largest telecom firms have 89% market share of wireless telecom. The top five players in grocery, by contrast, have a 79% market share.”

Karl Littler, Senior Vice President, Public Affairs at RCC

“There are grocery stores, confectionery stores, and independents on every corner of any decent-sized city in this country… I think there is far more competition in grocery store retailing than in the telecom market or airlines in Canada, to make a comparison.”

TVO/Ian Lee, associate professor at the Sprott School of Business at Carleton University

“What drove food prices higher? Pretty much everything. First, costs for raw food commodities that go into food production (things like wheat, wholesale meat, and oils) soared due to a perfect storm of adverse weather conditions and geopolitical turmoil. The Russian invasion of Ukraine sent wheat prices through the roof and caused a surge in prices for fertilizer and natural gas. And severe drought conditions hit the Prairie provinces, prompting domestic crop production to drop sharply in 2021.”

RBC