On November 17, 2020, the federal government introduced its proposal for a reformed federal privacy regime in Bill C-11, the Digital Charter Implementation Act (DCIA). (Long form title: An Act to enact the Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA) and the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act and to make consequential and related amendments to other Acts).

The first part of the DCIA replaces Part 1 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act(PIPEDA) with the proposed Consumer Privacy Protection Act. The DCIA also contains another Act, the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act (PIDPTA), which creates a new administrative Tribunal with privacy jurisdiction.

Why it matters to retailers

Bill C-11 in its final form would, once it passes, become the law generally governing retailer consumer personal information (PI) handling in all Canadian provinces and territories except B.C., Quebec and Alberta and all intraprovincial and international data flows.

The bill keeps some fundamental federal frameworks, but it introduces new elements including a mandatory privacy program, several new consumer protections and a more rigorous enforcement framework that includes compliance orders, AMPs and the highest privacy fines in the G7. Retailers should anticipate substantially higher compliance costs and consequences for non-compliance under the new regime.

Some of the more material changes in Bill C-11 are outlined below.

Privacy management program required

Retailers will now be required to have privacy management programs robust enough to handle the stronger privacy and data protection compliance requirements under the CPPA. As is generally the case under current rules, privacy considerations would not be limited just to what retailers do with PI “in-house.” Retailers also remain accountable for how third-party service providers handle PI on their behalf.

The federal Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) will be empowered to request to see a retailer’s privacy program. The OPC will also provide proactive feedback upon a retailer’s request.

Fines, another federal regulator and a private right of action

The CPPA would change the federal privacy enforcement framework substantially. The federal Privacy Commissioner would be able to issue orders to retailers for privacy violations and recommend significant administrative penalties (AMPs), up to 3% of global turnover or $10M, for a limited list of key infractions.

Bill C-11 would also establish an entirely new administrative Tribunal that would, unlike the Privacy Commissioner, be empowered to implement AMPs (the Commissioner can only recommend AMPs). This new Tribunal would also hear appeals from retailers, as well as complainants, of the federal Privacy Commissioner’s decisions.

The CPPA contains a private right of action too. However, this would not apply until a finding of CPPA contravention has been made and appeal avenues to the new Tribunal have been exhausted.

In addition, there are offences based on another small set of key infractions. These offences carry fines to a maximum of 5% global turnover or $25M, whichever is highest.

Stronger control for consumers over their personal information

As the Act’s title indicates, the CPPA places a strong emphasis on consumer data protection. For example, there is now a provision that empowers consumers to request that a retailer dispose of the PI the retailer has on that person, commonly referred to as a right to deletion. There are also requirements to identify and record purposes for which PI is collected, used and disclosed, to restrict PI handling to those purposes, and numerous other protections, both new and similar to those that already existed.

Some of the new fines and AMPs are based on infractions of these consumer protections.

Privacy policies

The CPPA will require retailers to use plain language in their privacy policies and outlines the type of information that they must include. This will include information on several new consumer protections in the CPPA, including exceptions to consent, automated decision systems transparency and requests to dispose of personal information.

Consent and exceptions to consent

Consent is still generally required as the basis for collecting, using and disclosing PI. However, there are now several exceptions to consent, including exceptions for standard business activities.

This is positive news for retailers, since these exceptions could, in theory, reduce consumer consent fatigue. For example, consent may not be needed to handle consumer PI related to common business activities like deliveries and returns. The CPPA provides for regulations related to these exceptions. Such regulations will potentially be an avenue to more granular, use case specificity on what will and will not count as exception to consent for retailers.

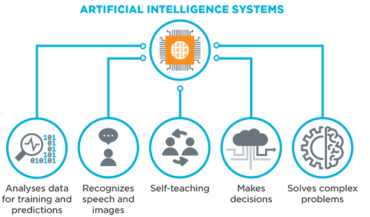

Automated decision systems

The CPPA will require retailers to share more information on any automated decision systems they use to handle consumer PI. The Act defines an automated decision system as any technology that assists or replaces the judgement of human decision-makers and lists various examples. In theory, the definition could potentially apply to such commonplace uses cases as a customer service system that automatically routes customer calls to the right department.

Individuals would be empowered to request an explanation from retailers of how an automated decision system made a prediction, recommendation or decision about them and how that system obtained their information.

Data mobility

The CPPA empowers a consumer to request that a retailer send that consumer’s PI to another organization. The CPPA does, however, take into consideration factors like commercial and technical feasibility, limits this right to other organizations also covered by a data mobility framework and provides for forthcoming regulations.

De-identification

De-identification is a technical solution often used to “hide” personal information contained in a dataset. In concept, although not necessarily always in reality given the technical processes used and innovations in data analysis, de-identification techniques can render PI unidentifiable.

De-identification has often been considered a way to remove PI from the scope of privacy laws, on the basis that such laws only apply to information that can identify someone and de-identification removes the possibility of identifying a person.

The CPPA includes a definition of de-identification and provisions related to it. However, as currently drafted, it is not clear that technical solutions to “deleting” consumer PI by de-identifying it will remain available. This could lead to a significant shift in industry practice.

Further context

Commercial privacy experts continue to explore the many nuances of Bill C-11, as does the Retail Council through its Privacy Committee and other avenues. We expect to share more over the coming months and welcome any questions or insights from retailers.

As retailers assess the CPPA’s full impact on their organisations, they should keep in mind the other, ongoing reviews and reforms of private sector privacy requirements in Canadian jurisdictions (Quebec, B.C. and Ontario, see RCC’s Privacy Key Issues page). The privacy obligations resulting from all of these may or may not harmonize with Bill C-11’s federal requirements in their final form.

For an overview of Bill C-11’s business impact from a legal perspective, with Quebec Bill 64 and European GDPR context, view BLG’s analysis.

More information:

For further information, contact Kate Skipton at kskipton@retailcouncil.org.